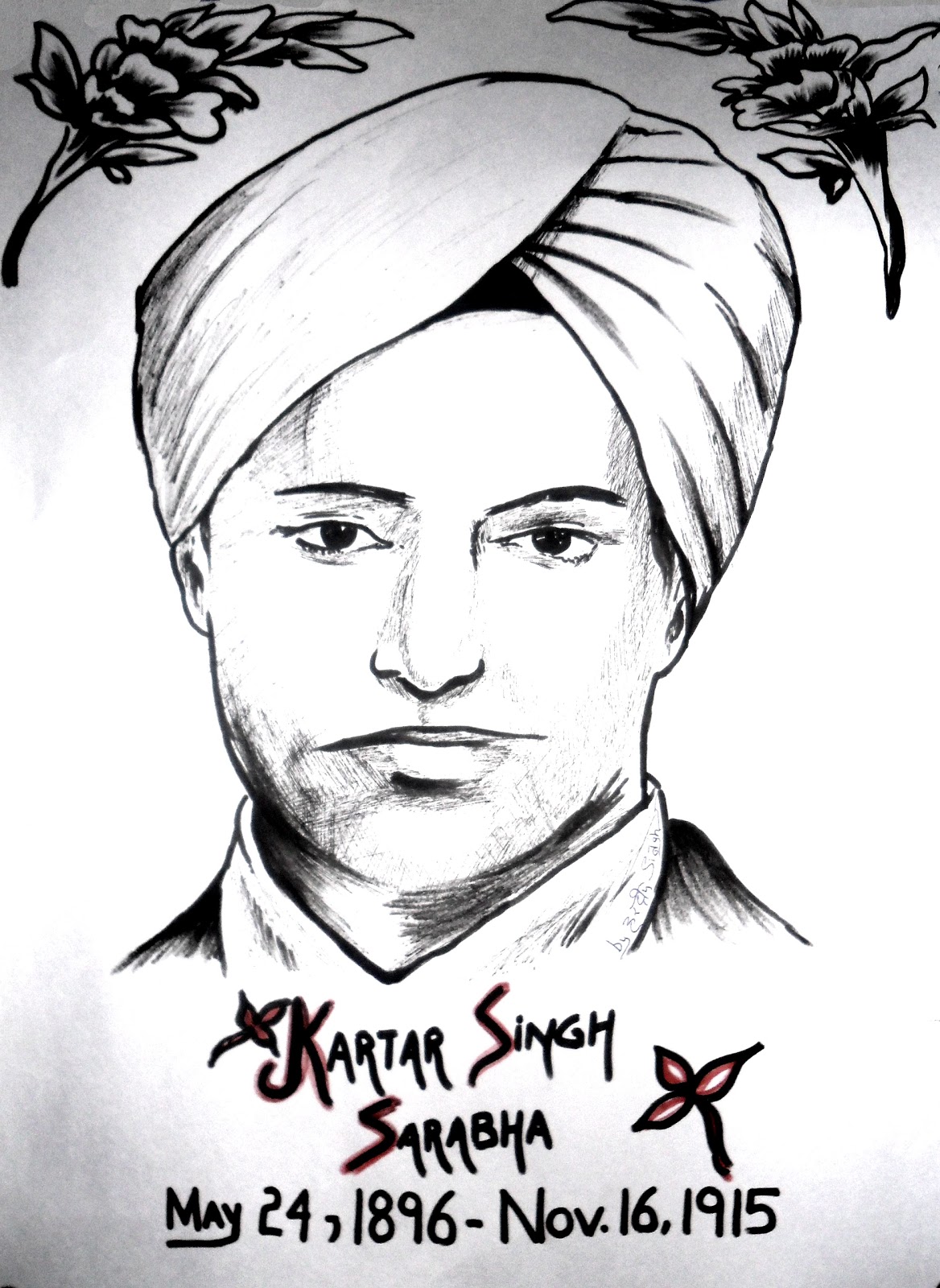

Kartar Singh Sarabha was one of the first to sacrifice his life for India’s freedom.

Born to Sahib Kaur and Mangal Singh, a Jat Sikh family of Sarabha, district Ludhiana, on May 24, 1896, Kartar Singh was the cherished son of loving parents. He lost his father in early childhood. His grandfather had brought him up. He finished primary education in his village school and completed matriculation from Mission High School. Later, he moved with his uncle to Orissa.

When he was 16, his grandfather thought it wise to send him to the U.S. for higher education and better prospects. The young Kartar Singh reached San Francisco with dreams of studying chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley.

Eyes full of dreams and a heart full of expectations, Kartar was totally unprepared for the welcome he got. At immigration in San Francisco, Kartar was subjected to humiliating questionings, bordering on a rigorous interrogation. He saw other Indians being subjected to similar treatment while other potential immigrants with obvious Caucasian features being let in with the barest of formalities. He asked someone sitting next to him as to why this was happening. “It is because Indians are slaves,” he was told.

WAKE UP CALL

This rankled the young, proud Sikh. “A slave?” he asked himself several times.

“Do I die this way? Or do I wake up and do something about what others think I am?”

Those questions surrounded Kartar. He knew that India’s stock in the world order had to go up. For that to happen, freedom was a necessity, no longer a mere dream. Something had to be done about getting that freedom. The fires of patriotism, nationalism and liberty began to burn bright inside the young man. And what he managed during his next three years is something ordinary folk do not accomplish during entire lifetimes.

Over the next year, Kartar Singh became a popular member of the Indian student community at the University of California, Berkeley. He had joined the Nalanda Club where he met other like-minded Indians and came to learn more about the injustices being meted out to the rest of the Indian expatriate community.

At the beginning of the 20th century, several Indians, especially Sikhs, had emigrated to the various British colonies. Most worked as farm labor. But even in these new lands, they were unable to escape the unequal treatment they had faced back home. They were still treated as second-class citizens and discriminated against in terms of wages. Kartar had also worked as a fruit picker alongside several other Sikhs. He knew of the racial slurs that were thrown at them. He knew of how they were paid less than other farm labor only because of the color of their skin.

GADAR MOVEMENT

When the Gadar movement was born in 1913, Kartar Singh became a key member. It was on 21 April 1913 that the Indians in Astoria, Oregon got together and formed the Gadar Party. They knew that there was no way they could claim a life of respect while India remained a British colony. Their aim was to overthrow the British from India, by any means possible.

They lived by the mantra, “Put at Stake Everything for the Freedom of the Country.”

Kartar Singh was put in charge of the party mouthpiece, Gadar, in Punjabi language. He wrote and edited the official Gadar in Punjabi and also printed on a hand-operated machine. Gadar was published in Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Gujarati and Pushto and went to Indians all over the world. It served to mobilize several to join the Gadar movement. Apart from news about the atrocities of the British, the newspaper also fuelled revolutionary ideas among the overseas Indians. The newspaper was published at Yugantar Ashram, the house in San Francisco which served as the headquarters of the Party and also as a place for the volunteers to live.

NATION CALLING

In October 1913, the Gadarites were at a meeting in Sacramento. Kartar Singh became so charged up with emotion and patriotism that he jumped onto the stage and broke into song.

“Chalo chaliye, desh nu yudh karen, eho akhiri vachan te farman ho gaye,” (Come! Let us go and join the battle for freedom, the final call has come, let us go), he sang.

He got his wish soon enough. When World War I broke out and the British were preoccupied with defending themselves, the Gadarites decided that the time for action had come. The decision of declaration of war against the British was published in the 5 August 1914 issue of Gadar. Copies of this issue were circulated among Indians everywhere, especially Indian soldiers in British cantonments.

On 25 January 1915, Rash Behari Bose reached Amritsar and went about assessing the preparations. At a meeting on 12 February 1915, the date for the revolt was set — 21 February 1915 was D-Day. The plan was to attack cantonments of Mian Mir and Ferozepur while Ambala was to be prepped for a mutiny. As the revolutionaries feverishly went about making their final preparations for the attack, they were unaware of a traitor in their midst. Kirpal Singh, a British mole, revealed the plan to his bosses and on 19 February 1915, just a day before the attack, the Gadarites were arrested. Kartar Singh, however, managed to evade the British. As the beleaguered Gadarites tried to take stock of the situation, it was decided that they should try and leave the country. Kartar was told to head towards Kabul. But the young man could not bring himself to flee while his comrades languished in prison. Ever the optimist, he made a last-ditch, desperate attempt to rouse the Indian soldiers of the 22 Cavalry at Chak No. 5 in Sargodha. He tried to incite the soldiers to mutiny. Rissaldar Ganda Singh of the 22 Cavalry, however, got Kartar Singh arrested.

He went to trial with the other Gadarites at Lahore in what came to be called the Lahore Conspiracy case. In September 1915, the sentence was pronounced — he was to be hanged till death. During the trial, Kartar Singh had refused counsel. While the judge was impressed by the young man’s intellect, he showed no mercy. He labeled the young boy the ‘most dangerous of all rebels’. The judge said, “He is very proud of the crimes committed by him. He does not deserve mercy and should be sentenced to death.” Witnesses say that the 19 year old sang patriotic songs all the way to the gallows, kissed the hangman’s noose, and embraced martyrdom.

At the age of 19, Kartar Singh, student, revolutionary, inspiring jewel in India’s freedom struggle, became Shaheed Kartar Singh Sarabha.