JAITO MORCHA, the name given to the Akali agitation for the restoration to his throne of Maharaja Ripudaman Singh of Nabha, a Sikh princely state in the Punjab. The Maharaja had strong pro-Akali sympathies and had overtly supported the Guru ka Bagh Morcha and donned a black turban as a mark of protest against the massacre of the reformists at Nankana Sahib. His contacts with the Indian nationalist leaders and involvement in popular causes had irked the British government. On 9 July 1923, he was forced to abdicate in favour of his minor son, Partap Singh.Â

Although the British officials pronounced his abdication to be voluntary, the Akalis and other nationalist sections condemned it as an act of highhandedness on the part of the government.Master Tara Singh denounced the measure as equivalent to Maharaja Duleep Singh`s removal from the throne of the Punjab. The committee set up to have the Maharaja of Nabha restored to the gaddi appointed 29 July 1923 to be observed in all the principal towns of the Punjab as a day of prayer in his behalf. On 2 August 1923, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee sent a telegram to Lord Reading, the Viceroy of India, challenging the official version that the Maharaja had relinquished his gaddi voluntarily, and seeking an independent enquiry to be instituted.

“The divan was originally scheduled to conclude on 27 August, but the arrests made by police provoked the Akalis to continue it indefinitely and to inaugurate a series of akhand paths or unbroken recitations of the Guru Granth Sahib.The police made more arrests and introduced at an akhand path on 14 September 1923, their own reader, Atma Singh, displacing the granihi sitting in attendance and reading the holy text. The sacrilege thus committed created a great commotion among the Sikhs. On 29 September the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee condemned the official action.

It simultaneously declared its determination to have the Sikhs` right to free worship reaffirmed, The government denied that the akhand path had been interrupted. Yet the jathds kept pouring in. The Secretary of State directed the Viceroy “to put an effective stop to the Akali operation by the arrest and prosecution of all the organizers as abettors.”The Punjab Government acting on the directive declared both the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee and the Shiromani Akali Dal as unlawful associations.

All the 60 members of the interim committee of the Shiromani Committee were arrested on charges of treason against the King Emperor. Akali jathds were stopped on entering Nabha territory, taken into custody and beaten by police. They were then left off in distant deserts without food or water. To intensify the agitation, the Akalis increased the size of the jathds. On 9 February 1924, 500 Akalis marched from the Akal Takht, receiving unprecedented welcome in villages and towns through which they passed.

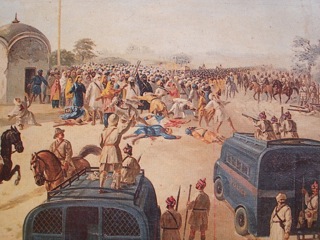

S. Zimand, a New York Times correspondent who witnessed the jalhd on the march, observed: “The Jatha was moving in perfect order and nonviolence with large crowds of public on its right and left, five Nishan Sahibs in the front and Guru Granth in the middle.” On 20 February 1924, the jalhd reached Bargari, a village on Nabha Faridkot border, barely 10 km from Jaito. AtJaito, about 150 metres from Gurdwara Tibbi Sahib, stood the Nabha administrator, Wilson Johnston, with a large force of state constabulary. On 21 February, the jathd marched on towards the Gurdwara, refusing to stop or disperse as demanded by Wilson Johnston.The administrator ordered the army to open fire, In two volleys of fire lasting about five minutes, several fell dead.

The official estimate of the casualties was 19 dead and 29 injured. The Akali figures were much higher. The firing on the peaceful jathd of Akalis caused resentment throughout the country. On 28 February 1924, another 500strong ShahldT jathd left Amritsar for Jaito where it was taken into custody on 14 March. Thirteen more 500strong jalhds reached Jaito and courted arrest.

Sikh jathas also came from Canada, Hong Kong and Shanghai to join the campaign.The Governor of the Punjab, Sir Malcolm Hailey, tried the policy of creating a schism in the community by having parallel Sikh Sudhar Committees representing moderate and pro-government sections. A 101strong jatha was allowed to perform an akhand path at Jaito. But this did not conciliate the general Sikh opinion, nor did it affect the tempo of the agitation.

On the issue of the Akalls being allowed to perform an akhand path at Jaito, the government was prepared to start negotiations through Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya and Bhai Jodh Singh, but it was adamant on the question of making restitution to the deposed Maharaja of his state.In the meantime, the Punjab Government introduced in the Legislative Council the Sikh Gurdwaras Bill which was unanimously passed on 7 July 1925. After the bill was passed, Sir Malcolm Hailey, Governor of the Punjab, announced during his speech in the Punjab Legislative Council that the Administrator of Nabha would permit the bands of pilgrims to proceed for religious worship to Gurdwara Garigsar at Jaito. Tlie announcement was followed by the release of most of the Akali prisoners arrested in the course of the restrictions on the performance of akhand path and the Akalis starting a series of 101 such recitations which was concluded on 6 August 1925.

References :

1. Ganda Singh, Some Confidential Papers of the AknU Movement. Amritsar, 1965

2. Mohinder Singli, The Akali Movement. Delhi, 1978

3. Salmi, Ruchi Ram, Struggle for Reform in Sikhi Shrines. Ed. Ganda Singli. Ami-itsar, n.d.

4. Hai-bans Singli, The Heritage of the Sikhs. Delhi, 1983

5. Pratap Singh, Giani, Gurduara Sudhar nrtliat Akali lehar. Amritsar, 1975

6. Josli, Solian Sirigh, Akali Morchidii da Jlihds. Delhi. 1972

7. Asliok, Shainsher Sirigh, Shiromani Gurdwara Prabnndhak Committee da Pnnjdh Said Itihds. Amritsar, 1982